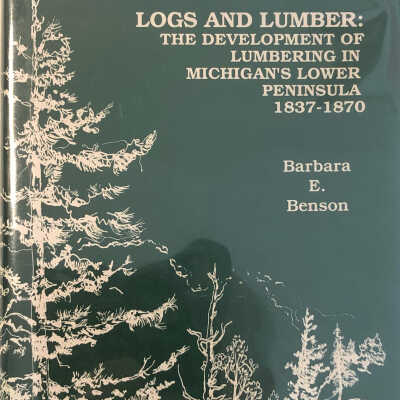

Log Marking Hammer

Double sided, log-marking hammer with a C and X stamps on the business ends. Head is likely cast iron. Very worn wooden handle. In the woods of Michigan, dozens of logging operations would cut millions of board feet of timber. Many of these were transported to the many mills along the streams. Moving logs from the forest to the mill would be handled by driving and sorting crews. Laws in the early 1850s provided equal rights to lumber companies and all persons using the rivers to float logs. As lumber activity increased, logs became mingled in rivers. It was hard to distinguish owners and some spilled their logs into the river forcing others to transport them downstream for a free ride. Laws became necessary for smoother operations. Bark marks, brand slashed along sides of logs, no matter how clear or simple, could not be sorted quickly enough with thousands of logs coming down river. Trying to read these marks, it frequently was necessary to turn logs over in the water. Finally, in 1859, a law required log owners who floated logs to mark the ends of their logs and to register these marks with the counties. End marks worked far better. They were stamped into the log ends with heavy marking hammers. Each end was marked in several places so the brand was always easy to spot. This 1859 law had a provision also to deal with log thievery. So many logs floating freely, representing easy money, were described as a constant temptation to thieves. Marks were often obliterated or cut off in order to give stolen logs another brand. In time, companies that transported logs down the river were confined to work just one river, and owners of logs floating them on the river were required to register their marks in the counties through which the stream passed. Log marks became not only devices of orderly transportation of timber to mills, but representatives of law in maintaining equities among the men who harvested the timber. From the Benzie County Record Patriot (March 22, 2000)