American Plan by Celia House

2022.16.25

First-hand accounts of Fishtown, Silver Lake, Reverend Gray, attitudes toward "fresh-air children" [Forward Movement Park campers] and townspeople. Very specific observations of plant and animal species, dune formation, river flow. Descriptions of town life including Memorial Day boat of flowers sent down the river, white and red lanterns hung every night to guide ship traffic in the channel, locals preparing for summer visitors, Fishtown, Indian Cut, steamship travel and more.

11 in

8-1/2 in

074 House Family

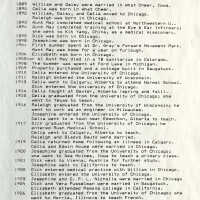

Allen, Katharine "Kiff" (House) 1926-2012House, Celia Martin (Gamble) (1890-1976)House, Edwin Harvey 1875-1958Gray, Reverend George W.Gamble, Clara Daisy (Bixby)

Presbyterian Camp/Camp Gray/Forward Movement Park 1899-2014

Excerpts from "American Plan" by Celia Gamble House https://sdhistoricalsociety.org/publications/NLHist/NLHist/P41-44.php SDHS newsletter insert pages 41-44 [Note: The William Gamble family of Chicago first came to Saugatuck in 1901 at the invitation of Dr. George W. Gray of Chicago who had recently begun the Forward Movement Camp, an operation designed to get poor children and families out of the cities in the summertime and give them an opportunity to live in the Michigan woods. He asked a number of Chicago families of higher social standing to attend also. In 1909 the Gambles built their own cottage on Riverside Drive, just south of what would become Camp Oak Openings (later Pine Trail Camp) overlooking the river and in 1919 their oldest daughter Celia, married Edwin H. House, a Saugatuck fruit farmer. Later in life Celia wrote an autobiography, couched in a fictional story of the family of Mary and Charles Vincent and their summers in the village of "Westport." Her manuscript was transcribed and edited by Katharine (House) Allen, one of her three daughters, who said that to her knowledge the story is completely factual. Below are excerpts from the 144 page book that relate to early days at what was to become Camp Gray, and life in a cottage on the river. The manuscript is accompanied by a list giving actual equivalents for fictional characters, for example Dr. Gray becomes Dr. White in the book. John Gardiner is the fictional equivalent of Edwin H. House, whom Celia (called Martha in the book) later married.] --- The trip was a delight to them from the last sight of Chicago, a string of lights winking out over the dark horizon, and the smooth crossing in the breezy little stateroom, to the early awakening on the Michigan side. A sudden slowing down of the propellers aroused them. They opened their eyes to the sun-flooded stateroom, whose white walls and ceiling were flowing with golden ripples reflected from the quiet water outside. They rushed to the porthole and saw a sight they never forgot, the shore of Michigan on a summer morning green and gold, with the sunrise above in the sky and below in the water. The heavenly quiet after the noisy docks and the throbbing of the engine all night seemed a tangible thing. No city, no wind, even. Just peace. Dr. White was like a lover introducing them to his lady. "It's good to have someone to share all this with me," he said. "The local people are so busy, and the people in the city wonder what I find to do over here, and why I like it so well." "Well, we can see why you like it," answered Mary, and, before the day was over, she saw what he found to do. As they walked along, he explained his method of path building, how he was trying to make level walks through the woods so that even those who were not climbers could enjoy them. The sandy soil was easily worked, and he cut shelf-like level stretches along the sides of hills, preventing the sand from shifting by driving stakes into the ground above and below and filling in the space above with brush. All the brush which accumulated from the necessary cutting was saved for this purpose, and the larger logs were used for steps where these were needed. They were secured with stakes driven into the ground below them and the ground between them was leveled. Keeping thus to one elevation involves a great deal of winding around the hills; so the paths were longer than necessary for arriving anywhere, easy, and breathtakingly lovely. The tents in which they lived were a delight, thanks to Dr. White's good mechanical sense, and they never knew how miserable tent life can be. For their tents were open at both ends to permit free passage of air; they were equipped with extra flies which made them proof against summer rains; and they were made a comfortable height for Mary by being set, not on the wooden platform itself, but on the edge of a twelve inch board which boxed in the platform, thus adding twelve inches to the height of the walls. The tents were pitched where they received direct sunlight a part of each day, and the platforms were raised sufficiently off the ground to insure dryness underneath. Both the platforms and the flies extended several feet in front of the tents to make a little sitting room where callers were usually received. Camp etiquette prescribed a discreet "halloo" when approaching a tent and the visitor stood at one side of the entrance until invited to enter. Meals were plain but ample, clothing plain and not too ample; floors were scoured by walking about on the particles of sand which seemed to be ever present. Life for Mary, thus simplified, became very full and rich. Every day they bathed in Lake Michigan. Nearly every evening they had a drift wood fire on the beach while the sunset faded and the stars came out. Early every morning Mary, from her bed, could see the fishing boats go out to the nets in the gray or rosy dawn. The charm of their free summers grew upon them during the long absence every year and Westport took on a glamour that never was on land or sea. Mary herself, felt the magic of wakening in Westport, so very far in spirit from the great, drab, hustling ever-alien city of Chicago. There was a soft lightness in the air, always a clear glow in the sunlight, a musical whisper in the trees that always welcomed them. It was fun, too, to return to a village where they were recognized and welcome. They did not yet know the feeling that the natives of a resort town have when the first summer visitors came back. It was more than anything else like the cheerful good morning that children give their teachers on the first day of school. It means that their personal and community lives are over until fall, that from now on they must hustle and not miss a chance to earn a dollar. It is their deadline toward which they have been gardening, painting, carpentering, spring cleaning, and sewing. Indeed, this deadline has been on their minds since away back in the fall when they began preserving and making jelly, and all through the winter while they quilted and made aprons and "fancy articles" for the church bazaar, held cannily in July. It means that they must move out of their neighborhood parties and club meetings must be suspended for three or four months, the end of leisure and the beginning of the campaign. However, it is easy to smile when old friends smile first and when they said, "Signs of spring, if here aren't the Vincents; it's nice to have you back with the birds!" they more than half meant it. So Mary and the children responded innocently to the greetings they received. Mary enjoyed the village people, feeling more at home in Westport than she ever had in Chicago. She liked their town meeting and the local observances of Memorial Day, when they sent a little ship made of spring flowers down the river in memory of their own men lost on Lake Michigan. She liked their enthusiasm over their gardens, the sun-time whistle that blew for noon at half-past eleven, and the technicalities of their talk which did not insult her with explanations of anything, but left her to find out what it meant to say that someone was "down to Buffalo layin' up a steamboat," "clamming half a mile above the slab island," or "down't the mouth." She gloried in a society where it was safe to address an elderly man as "Cap'n" and where the principal of the high school was "the Professor." She marvelled at the double delivery system required of the grocery stores who sent orders by river, if possible, in shabby little motorboats that made more noise than a lake steamer, and only if absolutely necessary, essayed the overland route with light buckboards and scrawny little horses. The stores were fun. There was one where it was possible to buy crockery, except that the proprietor always hated to part with the last one of any item, and a hardware store where all sorts of boatish things were sold. Although, at first, trips to the village were rare events and the business of life was in the woods or on the beach, as the children were more and more trusted with errands they learned to know the village for themselves. Jerry, especially was the young man about town who knew where boats were built, how the fish were marketed, what freight was going to Chicago each evening, and how to make himself useful to yachtsmen whose boats he felt honored to know. It was fun to board an old schooner and help unload firewood and they liked to go about noticing what changes had taken place since the last season. "They're tearing down -- tearing up -- or something -- the old Libbie Carter, Mom, you know, that tug? She's just a big skeleton now. A couple of men are working there." "And y'oughta see the signs in the woods where the path comes out on the beach -- you know, Mommie - - where the town kids used to put on their bathing suits? 'Anyone found dressing in the woods will be prosecuted for indecent exposure'!" Peals of laughter greeted this last and the charming phrase was immediately adopted for use whenever they thought they heard steps or voices outside their tents. "And there is another thing they should begin to know something about," [Mary] reflected, "and that is some practical notion of how work is done and what things cost." And so that is how it happened that she began taking them to visit the peach basket factory, and to watch clam fishing and boat building activities. The basket factory was situated at the head of the small lake where the logs were floated down the river in spring and collected in a boom. An endless belt carried them up into the building, huge black, dripping monsters like great hogs or walruses. There they were cut into lengths which were fastened at each end and revolved in a machine that sliced off large sheets of veneer. Then followed the cutting, nailing and packing. The smell of the wet sawdust, the screech of the saws, and the cleverness of the workmen fascinated the children. A tall Indian, who manipulated levers, charmed Patty for he wore a wild rose in his dusty cap. He belonged to a group of Potawattomies who camped nearby to work in the factory in summer, and spent their winters upstream trapping muskrats. The sandy bottom of the river was apt to shift and form sandbars. When this interfered with navigation, Federal engineers came in and dredged out the channel. They used a dredge mounted on a barge, and other barges on which the sand was loaded, to be towed out into the lake and dumped. A ship for living quarters completed their fleet which was of great interest to the children. They liked the cook and the cook's cat almost as well as the "drudge." The huge dredge splashed tremendously as it went down, and rose with its great jaws closed on a wagon load of sand. It then swung its dripping load over a barge and dropped it. In contrast to the rush and racket of the factory, and the immensity of the job done by the Federal Government, the clam fishing was the essence of peace and quiet. The fresh water mussels, locally called "clams," were thin shelled bi-valves, dark and rough outside and opalescent within. They were piled up in heaps in some secluded spot on the river bank to be sacked later and shipped to the button factory. The clammers rowed slowly along in flat-bottomed boats with their lines dragging hooks along the bottom. Even this job had its thrills, Mary discovered. Just shells for buttons were nothing to the clammers. They lived in hope of finding an occasional fresh water pearl. And once the Vincents had the fun of going out to the nets in the early morning with a fisherman in his sailboat. They learned to duck when the boom swung around on the tacks, and were much excited by the screaming gulls which followed the boat and swooped close to their heads as the fishermen dressed the fish and threw the offal overboard... Something seemed to be impelling them all [to move] from the fishing and hunting to the agricultural stage of culture. They had outgrown Eden and went forth of their own free will to earn further fun and experience in the real world. So Charles and Mary began to consider property. But before they bought anything, they did the one thing needed to make them fall, utterly and finally, in love with Westport. They spent a summer elsewhere. They went to one of the central counties to a small lake in the cutover pine region, of tamarack bordered lakes and sphagnum marshes, to live in a log cabin . They all missed the wooded dunes and beach of Lake Michigan. When Paul was fourteen and Jerry sixteen and a half, the children heard a good deal about correspondence with John Gardiner at Westport regarding a building lot. They remembered the Gardiner place vaguely, as bordering on the river which had been their highway, and they knew very well the high bank facing westward which commanded a fine view of the mouth of the river. After what seemed like a long time, the bargain between Scotch-Irish Charles and Yankee John Gardiner was made and Mary and Charles began drawing plans for the cottage. A Westport carpenter was engaged and as soon as spring opened, Charles and Mary began taking weekend trips over to inspect the work. The family rejoiced that their loyalty to Westport was now renewed and made permanent. A boat was to be a necessity if they were to keep house so far from the village. So after poring over catalogues and conferring with salesmen, they chose their boat. It was a twenty-four foot open run-about with an exposed engine amidships and a canvas top which folded back onto the stern deck. They named it Uncle Dan, because Uncle Dan has "swum every stream he come to till he come to the Mississip'." Charles sent [the boys] around the shore of Lake Michigan to Westport in the Uncle Dan. Of the wind that came up after they started and his anxiety about their safety, he never liked to speak afterward. He paced the floor and fretted and drove Mary almost to distraction. Mary had to pack for the annual migration whether she was worried or not. They made the night trip and arrived in Westport before the boys and their boat. Soon, however, John Gardiner set their fears at rest by arriving with a telephone message from the sailors saying that they had spent the night in a harbor to the south and were starting on the last lap of their voyage. +++ They were down at the river shore planning [a pier] when the staccato notes of the Uncle Dan engine broke the stillness. Mary and the girls hurried down from the cottage and joyful shouts from shore answered the toots of the little whistle and the clamor of the ship's bell as Uncle Dan swept up to a point in line with the pier site. The boys were eager to see the cottage and climbed up the bank with Mary and the girls. The cottage was all fresh bright golden pine boards, fragrant still with shavings and sawdust, and full of vagrant breezes from the many windows, every one of which framed a picture of tree branches spotted with sun and the shadows of waving leaves. "And come out here to the sleeping porch," said Martha, pointing out over the sloping ground to John Gardiner's orchard. Seen from above, it was a rug of freshly turned earth dotted with the round bushy tops of the apple trees. The cottage was set on the top of a ridge which paralleled the river, so that the ground sloped steeply down to the water's edge on the west side and more gradually to the orchard on the east. At that hour, the cool lake breeze fanned the shady western slope and the morning sun glowed on the eastern side where Mary's garden was to be... That evening, as Mary served a buffet supper from the top of a trunk, to a family seated on the edge of the porch with feet swinging, the Chicago steamer, on its way down the river passed so close under their bank that Judy said, "I could throw a biscuit down onto the deck." The lighthouse at the mouth was plainly visible from the cottage and the harbor light, a red flash, dark fifteen seconds, a white flash, and again dark fifteen seconds, oriented then even on the darkest night. Uncle Dan served them well enough for three or four summers, but at last they were writing for catalogues again and seeing boats in their dreams. The second boat, also Uncle Dan, was longer and trimmer. She carried no top to catch the wind and she cut the water with a higher plume of spray on each side of the ten foot forward deck. The motor was under this deck, which left the cockpit clear for chairs and protected light frocks from motor oil. The girls began to run the new boat as it was more reliable. Changes came in the cottage, too. A guest room became a necessity, so they contrived a room below the sleeping porch which was well off the ground, due to the slope. It was a family enterprise and Martha was helping one day with the painting when Charles saw a good sized snake glide under the floor. He warned Martha, but she was so intent on her work that she kept painting. Charles was delighted and the guest room was immediately dubbed, "The Snake Room." A series of cooler summers made the family falter a little in their devotion to breezes. It became evident that the river valley was a draw for lake winds, and all their jutting walls, provided with only screens and awnings, were wind traps. Charles weakened to the extent of having a small glassed in room built at one end of the sleeping porch. This was called "Dad's Hot Box," but it was hot `only by contrast. At last the peach and sweet cherry trees, set out under the neighborly guidance of John Gardiner, began to bear and there was a small but thriving strawberry patch. When Mary picked the first basketful of huge fragrant strawberries and sat on a garden bench to rest and cool off, with all this wealth in her lap and yellow roses and forget-me-hots right at hand, she felt that no one could be happier than she was at that moment. --- [ Note: The family continued to use the Gamble cottage in the summertime for many years, but it has since been sold although it still stands, little changed. The House house, on 66th Street, remains in the family, occasionally inhabited on a year-round basis, by some corner of the family, always a favorite gathering place in the summertime.]

03/09/2022

11/08/2023