Avalon, the Harbert Cottage

2023.10.357

Digital scan

Avalon, Harbert CottageHarbert, William Soesbe 1842-1919Harbert, Elizabeth Morrison (Boynton) 1843-1925

In Arthurian legend, Avalon is the place to which King Arthur was conveyed after death. Some of the land where the Avalon cottage once stood was purchased by Thomas Eddy Tallmadge whose estate donated it to Ox-Bow. Later the land was sold Saugatuck to relieve the school's tax burden.

Buildings: LostBuildings: Homes, cottages and private residences

Winthers, Sally

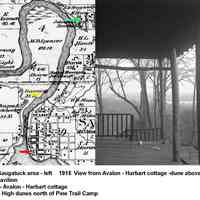

Digital data in CatalogIt

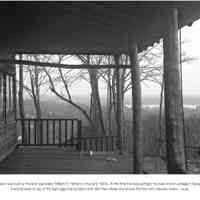

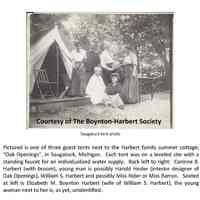

THE AVALON From the first moment I saw the photos of the Avalon, I wanted to know more about it. You might say that this structure must have been the best seen cottage in Saugatuck. Poised on the skyline, on a stunning vantage point atop the high ridge that borders north Park Street across the river from Moores Creek. It commanded a view of both Lake Michigan and Lake Kalamazoo. To reach the location one must start up the road leading to the water reservoir located on the north shoulder of Mt. Baldhead. About fifty yards up, a branch of the road goes to the right and heads steeply up the front of the bluff overlooking the river. Immediately at the top are the remnants of the Avalon foundation. Unfortunately, today the view is lost to the surrounding foliage. The history is interesting, especially so since we are now learning about the family that built it. The Avalon was built by William Harbert (1843-1920) and his wife Elizabeth Boynton (1845-1925) in 1905 for their daughter Corrine. Their home was in Evanston, Illinois but they obviously had affection for Saugatuck. William Harbert was a successful attorney in Chicago. He founded the law firm of Harbert and Daley which specialized in right of way work for railroads in the period 1880-1910. As a personal investment, he bought a great amount of land in the Saugatuck area, including a large parcel surrounding the Avalon location. Elizabeth Boynton was a PhD, a successful writer and was very highly regarded for her leadership activities in the National Woman Suffrage movement. The great great grandson of the Harberts, Bill Frederick contacted me at the SDHS last April. He was here from California gathering information on the Harberts. He knew of the family connection with Saugatuck and wanted to see the town and the Avalon site. I was pleased to oblige him with a tour and we exchanged historical information. I was anxious to know what happened to the Harberts and to the Avalon. Stay tuned for more in next month's newsletter. submitted by [email protected] June 2012 SDHC newsletter

These image(s) were copied from the SDHC photo blog [or the Jack Sheridan drive if that was a superior version] in preparation for updating the SDHC website in 2023.

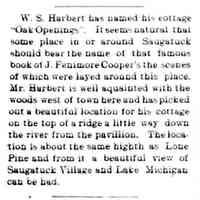

Biography of a House The house was unusual for many reasons. Its location seemed odd, almost inaccessible in this era of motorized transport; it stood at the top of a long uphill footpath. It had peculiar scars which were not immediately visible to the casual observer, but it could be seen on close examination that at some time the house had undergone major surgery of a startling kind. In style it was not remarkable: plain, rustic, foursquare, unimaginative -- but larger than might be expected of a simple country cabin. Originally named Oak Openings, it was known to many local people as Avalon Cottage, to teenagers and transients as The Haunted House, and to us, its closest neighbors simply as the Old House. It had at least 4000 square feet of living space including six bedrooms and a loft which contained two double beds. Completely furnished when I first saw it, its ambiance was very much that of a pioneer dwelling, with many obviously handmade pieces. Chairs and tables were cleverly put together from saplings, peeled branches, grapevine, and polished slabs of tree trunk. In the midst of these rustic surroundings, a fabulously elaborate grand piano made of rosewood, delicately carved and inlaid, seemed strangely out of place. Although it was a house well-loved by its many guests, absentee ownership, indifference, neglect, the Great Depression, the weather, and an undeserved ghostly reputation caused its shockingly swift decline and decay. The Avalon was perched on a high dune overlooking the west bank of the Kalamazoo River across from Moore's Creek It was built around 1900 -- give or take a few years -- by one of Michigan's last land barons, William Harbert. For a long time, he had acquired and continued to own great chunks of property all along the Lake Michigan shore. Travelers on the secondary roads and highways that parallel a 200 mile shore line still run across his name frequently, memorialized in parks, hamlets, and local streets. For his own vacation lodge in the forest he chose what he considered the most beautiful location of all: a high knoll on a heavily wooded hill between Lake Michigan and the Kalamazoo River across from Saugatuck. Views in both directions were spectacular. Even the hill site which he gave to the local town council for a needed water tower was appreciably lower than his lot. The water pipes serving the house actually had to emerge from the huge tank halfway up its spherical surface. The hill itself was probably about 150 feet high, and very irregular in conformation. The trees and vegetation that covered it were, at the very least, a couple of hundred years old, and the root, leaf mold, and decayed vegetation layer was thick, but underneath, the hill was unmistakably an old sand dune, with long curving ridges, deep ravines, and unexpected hollows. When the house was built, the transportation difficulty that later developed had not yet been foreseen. Then, horses could easily pull wagons on the sandy track that led upwards, and people could be delivered to the door in a light buggy. As the high swirl on which the house was sited was long and narrow, Harbert designed his lodge to be long and narrow also. It was to be about 75 feet long by about 25 feet wide, in two stories. Since the ridge on which it was to stand was clearly only sand, though deceptively firm-looking, a very strong foundation was constructed, utilizing the wealth of smooth, rounded stones thrown up on the beach by fierce Lake Michigan storms. The stones selected were approximately the size of a football. Fitted neatly together with cement, they formed a reassuring base, visible from the rear of the house, but not from the front, which was even with the top of the ridge. The same kind of stones formed a tall chimney serving a baronial stone fireplace on the first floor and a slightly smaller one upstairs. According to the original plan, you entered the dining room, a room at least 25 by 20 feet, dominated by its fireplace. A corridor led the length of the first floor, serving four small bedrooms, a bathroom, an enclosed stairway to the second floor, and the kitchen, which, without electricity, boasted a neat kerosene stove and a shaft through which shelves could be let down by ropes to a cooler place. Some of the bedrooms had doors leading outside to rustic balconies. Upstairs was a huge lounge or living room, occupying two thirds or more of the length of the house, and its entire width. At one end stood the stone fireplace, and at the other, a spacious loft bisected by a central stairway. Intended for overflow sleeping quarters, it was furnished with two double beds, one on each side of the stairhead, and each one backed by a commodious walk-in storage space serving, among other things, as closet and cupboard for the loft dwellers. Between these two enclosed closets was a short corridor leading to a window on the north wall. As the loft was completely open at its front, except for a rustic railing, and the great hall it overlooked was all windows on the western side, there was plenty of ventilation. Under this loft, and closed off by a door on each side of the stair, was a kind of master suite comprising two rooms and a bathroom. Although not large, this section of the house presented a more finished look than the rest. It was paneled and appeared to be winterized. An old-fashioned pot-bellied woodstove stood in one corner. If he wished, the owner would have been able to stay in the house for short periods even in cold weather. The rest of the building was of simpler construction, with bare joists and beams, suitable only for summer occupancy. As a building design, it was not beautiful, and its height soon proved impractical. Perched up there on its knoll, it must have resembled a monstrous, brown cereal box sticking up above the tree tops. It was too high, too narrow, and insufficiently reinforced to withstand the gales that often blow off the lake. Windows blew open or rattled their panes loose, cracks appeared in corners and around the chimney, and an examination of the heavy, stone foundation revealed that the force of the wind had caused a faint shift even there as the upper story swayed. Something would have to be done. After much dithering, the problem was solved in a surprising way. A young carpenter, a local man who was already known for his quality work and his independent attitude, proposed to slice off the top story and relocate it in front of the first floor. Although this sounded like an impossible task, it was finally accepted as the only suggested solution which might have any chance of success. The carpenter had a reputation for quick thinking and resourcefulness. What he said he could do he could usually accomplish, and he said without boasting that he would be able to decapitate the structure, reassemble it in a new form, and leave it in fine condition for many years of use. Furthermore, he would accept no time deadline, preferring to work almost single-handed, hiring what little extra muscle he would need for any especially crucial aspects of the job. He would not work fast, but he was sure that his results would be satisfactory. They were. He rigged a block and tackle arrangement to support and evenly distribute the weight of the second story. Most of the time, as he had promised, he worked alone, needing help only from time to time to tighten the ropes, or to move his temporary scaffolding to its next position. The actual "surgery" he did with an ordinary hand saw. When it was time to transfer the top part of the house to its new location, on deep-set posts directly in front of the original first floor, he hired a team of farm horses to supply the necessary power. The join was hardly noticeable. Where the heavy Dutch-style front door had led directly into the dining room, there was now a French door opening into the great hall. The Dutch door itself was simply moved across the living room, taking the place of one in a long row of windows. What was now the rear part of the house was given a flat roof and a rustic railing, forming an extensive deck, which actually sported its own outdoor fireplace. The worst scar was that of the south wall in the living room. It was here that the stone fireplace had stood, now left behind on the deck, and the replacement wall presented a rather stark, barn-like appearance. Also, the floor at that end of the long high-gabled room was raised, making a kind of platform or dais, which may have originally surrounded an elevated hearth. To utilize, beautify and give purpose to this, the only disfigured part of his house, Mr. Harbert decided to bring into these rather primitive surroundings an astonishing contrast, a magnificent example of cabinet-making and instrument-making art. The Viennese grand piano, constructed of carved and inlaid rosewood, and fit to grace a palace, had recently been on exhibition at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Placed on that dais, it successfully drew all eyes. It gave the great hall a balance that the loss of the fireplace had destroyed. That it was also criminal treatment of an irreplaceable object of beauty seems not to have occurred to its autocratic owner. Judging by the stories that were told me by older people who had known the place in its heyday, it must have been a very happy house, often filled to capacity with guests, many of who made lengthy stays. Mr. Harbert was so fond of surrounding himself with agreeable company that he prepared three leveled tent sites close by, each with a standing faucet, for a convenient, individualized water supply. Even after Mr. Harbert's death, many of those who had best known the house continued to vacation there, renting it for different periods of time during the summers. His heir, a daughter, had moved to California and seemed to take little interest in the condition of her property. Although she accepted -- indeed, required -- rent from former guests, it never seemed to occur to her to prepare the house for their tenancy. The renters themselves took that responsibility as a labor of love. As time went by, however, these people began to find it increasingly difficult to get up the hill with their luggage, and to stock the larder. They were getting older and no longer felt like roughing it. Horse-drawn transport had given way to the automobile, and cars were useless in the sand. Walking was the only way up, and while not steep, the footpath was long. Also, letters to the owner about the need for minor repairs were simply ignored. The house, always empty in the winter, was soon largely abandoned in the summer too. Only one stubborn die-hard continued to pay two weeks rent for a "vacation" which she spent nostalgically cleaning and refurbishing the old place, while her two boys played Indian in the woods. As with any empty and apparently deserted building, the curious, the souvenir hunters, the thrill-seekers and the romantics seem to feel impelled to seek entry. Where one break-in has occurred the next is easier. Although some local people took an interest in trying to keep it locked up, the house was in an isolated location, and it would sometimes be found to have been left open for several days in rainy or windy weather. Its neglected appearance gave passing hikers what they considered carte blanche to appropriate anything moveable. Because of broken locks and missing window panes, it soon became truly impossible to close the place up. Ghost hunters crept in frequently to scream at creaking timbers, tilted floors, and unexpected shadows, and, like the other unauthorized visitors, they were not empty-handed when they left. Letters to the daughter in California still elicited no response, and finally, even the faithful "caretaking" tenant had to give up. By this time the roof leaked in a dozen places, and the floor under the oldest leaks was rotten and unsafe. The rear part, despite or perhaps because of its heavy foundation, had developed a definite list, so that the kitchen could not be used, even if there had been anything left of a once large supply of dishes and utensils. Furniture had been carted away, piece by piece, or burned in the crazily slanted fireplace during "parties." Finally, only the piano remained, like a bedizened Miss Havisham in the midst of decay and destruction. The vultures couldn't move it; not until some one of them conceived the notion of hacking off pieces of carving and elaborate inlay. Like a body attacked by piranha, the piano was then quickly reduced to its inner workings, which lay broken and hardly identifiable on the splintery boards of the dais. Shortly after the end of World War II, after having stood too long as a broken shell, an attractive nuisance, and a fire hazard, the house was finally torn down and its boards carted away. Taxes on the property had not been paid for many years, and the local town council took what it saw as necessary action. Although long looked on as ancient, the structure had actually lasted fewer than fifty years up there on its hilltop knoll. Its passing was, ironically, never understood by the one person who could have prevented disaster. the Harbert daughter, many years too late, arrived on the scene, breathing empty threats of litigation in her futile search far something she herself had allowed to melt away. The house was gone, but not forgotten, even today. It was an unusual house. - Helen Gage DeSoto

11/05/2023

10/21/2024