Mersback property abstract and family stories

2023.50.87

SDHS NL InsertsFamily History1830 Settlement, pioneer era

Winthers, Sally

Digital data in CatalogIt

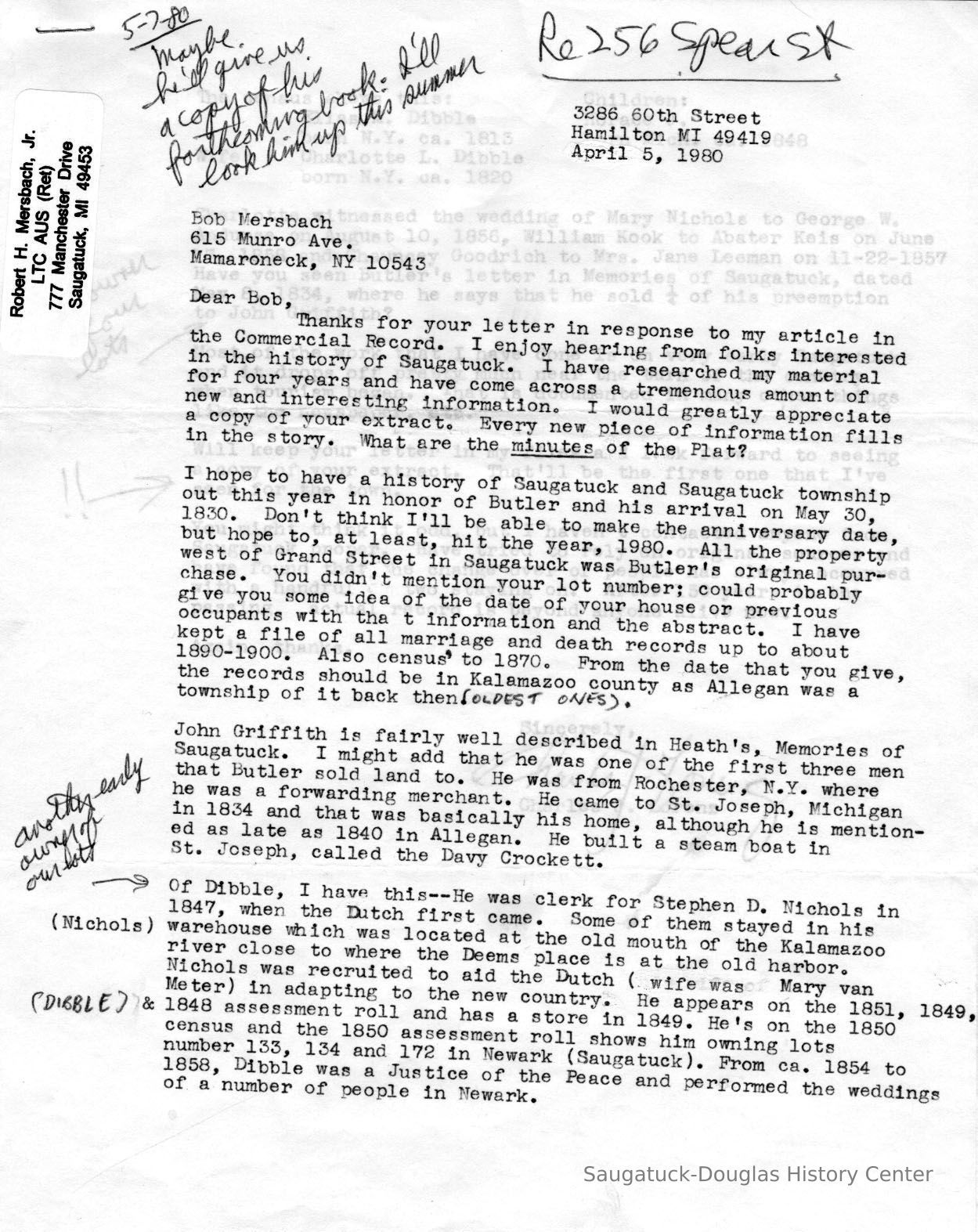

Mersbach, Robert "Bob" Herman Jr. 1924-2008Mersbach, DorisLorenz, Charles J. 1942-1994Dibble, Elias M. 1813-1859Griffith, John c1800-?Helmer, Robert W. 1826-1885Vosburgh, Armenius c1820-1883Mead, John Eldridge 1822-1901Richards, Jacob J. 1837-Greenhalgh, Alonzo R. 1847-1893Barber, Daniel L. 1840-1909Pond, James Munroe 1823-1900Butler, William Gay 1799-1857

This information was OCR text scanned from SDHS newsletter supplements. Binders of original paper copies are in the SDHC reference library.

Last Cavalry Charge on Butler Street by Bob Mersbach In 1944 I was stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas; a member of the 129' Cavalry Squadron, the last mounted unit in the U. S. Army. (Although there is still an Old Guard mounted unit, used for parades and funerals, we in the 129t" were the last in the regular army.) That summer a fellow trooper, Alex Burduck, and I took a three-day pass over a long weekend. Since Sunday was a free day, that gave us four days off. We left Fort Riley in a boxcar fixed up with wooden benches and hooked onto a Union Pacific train, got off at Kansas City and took the overnight train to Chicago. There were no seats available (the trains were full in those wartime days of gas rationing) and so we and others spent the night in the vestibule between cars, where it was noisy, bumpy, cold and windy. From Chicago we took the Pere Marquette Railroad to Fennville, where we were met by my mother who drove us to Saugatuck to my grandparents' house on lower Spear Street. My sister was a summer camper at Camp Oak Openings near the mouth of the Kalamazoo River and we visited her one morning. The man in charge of the camp's horse riding program was a Mr. Zeiser. In World War I he had been a horse cavalry officer and later a dirigible captain in the German army. When he saw our boots and breeches his face lit up and he offered to take up on an extended horseback ride. For most of the rest of the day the three of us rode all over the area - the sand dunes, old Singapore and Saugatuck. We were walking the horses from Lucy Street down Butler street in downtown Saugatuck. When we got to the hardware store (then Koning's, now Wilkins) Mr. Zeiser noted that the street was empty of auto traffic. In 1944 gas rationing was in full effect and the auto traffic was notable by its literal absence most of the time. Mr. Zeiser then suggested that we take a full gallop right down the middle of Butler Street to the Saugatuck Village Hall. Alex and I instantly agreed, and away we charged. All that we lacked was a bugler. At a full gallop the hooves of the three horses made quite a racket on the concrete street and pedestrians and shoppers stopped in amazement. That charge got the attention of just about everyone along Butler Street and was the highlight of our visit to Saugatuck. As it turned out Alex and I haven't seen each other since 1945, nearly 56 years ago. He's lived m Brooklyn all his life. We still write each other and send Christmas cards, and an occasional picture so that we'll recognize each other if we ever meet again. Source: SDHC newsletter insert page 204

Potato Shooters by Bob Mersbach My grandparents, Frederick William and Helen (Crafts) Job retired to Saugatuck. He was an attorney in Chicago and they had owned a cottage in Macatawa from the turn of the century until the middle 1920s when it burned in one of the big fires. During the summer my mother and her sisters would board the trolley (Interurban) at Macatawa and get off at Saugatuck's Big Pavilion for weekly dancing. Grandpa was about to retire when the cottage burned and, because the whole family liked Saugatuck, he had a big frame house built next to All Saints Episcopal Church and retired to it in 1927. The house has gone through several owners and is now owned by the church. We loved our vacations in Saugatuck and it was at their retirement home that he taught us grandchildren how to make potato shooters. Back in 1932 or 1933 it was the depths of the Great Depression, and although pea shooters were only 10 cents and a supply of hard peas another dime, they were considered to be rather expensive; especially as you could shoot a dime bag of peas in a few minutes. To make potato shooters, Grandpa would first take us to the beach where we gathered sea gull feather quills. Then, at his garage work table he'd snip off the quill part, ream it out with a pipe cleaner and send one of us to the kitchen to sneak out a couple of potatoes. He'd peel them and we were ready for the fun. You'd stick the quill into the potato and pull it out with a quick sideways motion. A bit of potato would stick in the quill. You'd put the other end into your mouth and blow suddenly with some force. If you did it right you'd get a good distance with the potato bit. The potato shooter had several advantages versus the pea shooter. The potato shooter and the ammunition were literally free, the potato pellets were harmless (a shot pea could seriously damage one's eye), and because the potatoes were starchy, the bit usually stuck to whatever they hit. This last was both an advantage and a disadvantage. They stuck to what they hit and so the one who got hit couldn't very well claim a miss, but we'd sometimes shoot potato bits inside the house and they'd stick to lampshades and windows. Grandma would see them and immediately holler: "Frederick, you take those children and those nasty shooters out of the house, and STAY OUT!" In spite of those little unpleasantries, we had a lot of fun with those potato shooters invented by a really "great" grandfather. -- Robert H. Mersbach Jr. Bob adds, "After my grandfather died in 1935 potato shooters sort of died out, and they were not resurrected until at a family get-together in 1990 we tried them again with some success. Source: SDHC newsletter insert page 52

11/27/2023

11/28/2023